Sweet Alice

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lobularia_maritima#/media/File:Smagliczka_nadmorska_1.jpg |

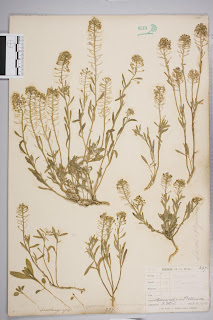

“Sweet Alice” is the common name for Alyssum, whose scientific name is Lobularia maritime, a species of low-growing, mounded plant bearing many branches of tiny flowers gathered in round clusters (Hogan 833). Composed of four rounded petals, Sweet Alice flowers are most often white or cream-colored with some garden cultivars bearing pink to rose-violet blooms; they are known for their sweet scent, resembling honey. Alyssum generally begins to bloom in June and can grow to the height of a foot. The Wikipedia entry confirms that the name maritime denotes its “preferred coast habitat” and states that it is “common on sandy beaches and dunes.”[1] The website of the Cornish Biodiversity Network notes that it often grows “on walls and in pavement cracks,” and asserts that “It is very frequent around Hayle.”[2] This dried specimen, gathered at St. Mawes on the eastern side of Cornwall in 1900, shows that it can be quite tall and rangy.

Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland: Herbarium

http://herbariaunited.org/specimen/315618/?image

Boasting that it is the “Ultimate Guide to Alyssum Flowers,” a somewhat Wiccan website “The Petal Republic” suggests that the name “Alyssum” comes from the Greek for “without rabies,” now generally translated as “without madness,” and that wearing it can help “cultivate calmness and avoid anger.” Perhaps more helpful is its historical observation that Allyssum’s “role in the floriography pantheon among the sweet” flowers, meant that alyssum was particularly appropriate for children.[3] Like Kate Greenaway, the site assigns “worth beyond beauty” as the significance of “(sweet) Alyssum” in the Victorian language of flowers (Greenaway 8). Other than this, I can find no literary or mythological references to “Sweet Alice” or “Sweet Alyssum” or “Alyssum,” suggesting that the modest nature of its appearance and habitat did not inspire poetic use.

Woolf mentions “Sweet Alice” three times in her fiction, each time associating the flower with young girls who pick it in locations somewhat redolent of Woolf’s own childhood summers in Cornwall. In the 1925 short story “Ancestors,” one of several spin-offs from Mrs. Dalloway that explores the consciousness of characters present at the party with which the novel ends, Woolf enumerates Mrs. Vallance’s flower-filled memories of her childhood at home in Scotland where she “had run wild through the currant bushes” “picking Sweet Alice,” and then had sat up in her bed in the attic reading all of Shelley (CSF 181, 182). Her over-idealized memories shield her from the unpleasant present like a valance or dust ruffle, behind which she is able to live more vividly in the past.

The image of the wild girl-child running through the garden reoccurs in the 1927 novel To the Lighthouse, where Cam Ramsay, like Virginia Stephen the youngest daughter of the family, is pictured “picking Sweet Alice on the bank” (TTL 25). Like the young Mrs. Vallance, as a girl Cam is something of rebel; “wild and fierce,” she refuses to fit into traditional gender roles and will not give away her flower even to the benign Mr. Bankes, causing him to call her “Cam the Wicked” in his fond litany of family nicknames (TTL 26). In the third part of the story, however, Cam’s wild energy has become muted, in part by the tension between her own desires and her deep allegiance to and love for her father; described by Elizabeth Abel in her brilliant psychoanalytic analysis of Cam as dramatizing “the narrative plight of the daughter who thinks back through her father” (“Cam the Wicked,”172).

Another young girl, the alienated and eventually suicidal Rhoda in The Waves, seems to bind together elements of both Mrs. Vallance and Cam. Although less wild and more contemplative than either of her predecessors, she too picks Sweet Alice. In her “short space of freedom” before lessons she creates a micro-world in a bowl of water by floating and arranging various flowers: “I have picked all the fallen petals and made them swim. I have put raindrops in some. I will plant a lighthouse here, a head of Sweet Alice. And I will now rock the brown basin from side to side so that my ships may ride the waves” (11). While imagining the tall spire of alyssum as a lighthouse hearkens back to her earlier novel, like Mrs. Vallance of the short story, Rhoda is an avid reader of Shelley. Another connection between The Waves and To the Lighthouse, is revealed by Sayaka Okumura’s detailed article on Rhoda’s references to Shelley’s poem “The Question,” which ends with the narrator gathering up a bunch of flowers in a “nosegay,” and then asking “to whom” it should be given.[4] Twice in the novel, Rhoda asks “to whom” she should give the blossoms of her imagination: once in the second episode when she reads poetry before going to sleep to dream of Miss Lambert (TW 40), and then again at the end of episode seven when she describes her own suicide (TW 151). It seems that Rhoda has internalized Cam’s quandary about whether she should give her flowers to the gentlemen. Like all of the young girls who gather alyssum in Woolf she is a sweet Alice who inhabits a wonderland slightly alienated from the realities of adult gender roles and identities.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lobularia_maritima Accessed March 15, 2022.

[2] https://www.cornishbiodiversitynetwork.org/wpages/CBNM805.htm Accessed March 13, 2022.

[3] https://www.petalrepublic.com/alyssum-flowers/ Accessed March 15, 2022.

[4] For text of poem see https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45138/the-question-56d224839110e Accessed March 19, 2022.

No comments:

Post a Comment